As we plan for the upcoming school year, it’s a good time to reflect and think about goals and the means to implement them in the next few months. Many colleagues have mentioned the desire to incorporate more technology and even go so far as to suggest a “paperless classroom.” It sometimes seems like a race to keep up with the latest advances in technology as they impact learning via animations, simulations, apps, probeware and flipped learning to name a few. While I too am guilty of falling victim to the allure of any tool that appears to potentially enhance my students’ love of learning science, the replacement of a traditional aspect of a lesson’s design should be performed only if it offers a real and tangible improvement to the lesson. The excessive use of technology simply based on trends should be approached with caution.

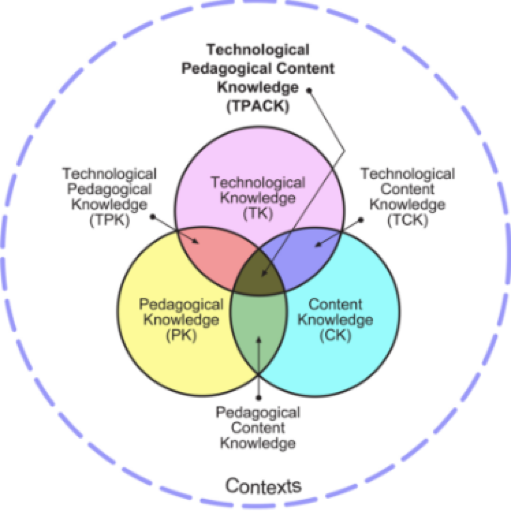

Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPCK) can be the vehicle by which teachers decide if and how a technological application can be incorporated into their classrooms. TPCK more recently coined as TPACK technology, pedagogy and content knowledge incorporates technology into Lee Shulman’s pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) construct (Mishra, P., & Koehler, M.J., 2006). PCK is the means by which a teacher takes his/her content knowledge and transforms it into content knowledge for his/her students. Teachers’ PCK includes an understanding of the misconceptions and preconceptions students bring to each specific topic as well as the strategies to assist them in overcoming these barriers to student understanding such as demonstrations, animations, simulations, analogies, etc. (Shulman, L., 1987). With technology constantly evolving it is important to utilize applications with students if and when they enhance student learning. When deciding if it is appropriate to utilize a particular technology tool, a TPACK lens requires a teacher to think about how the technology could be used as a pedagogical tool or content representation as well as how student learning of the content is impacted by such a tool when considering the context of how it would be used. In other words: it eliminates the thought process of using technology for the sake of technology but rather requires purposeful lesson design where technology is integrated if and only if it aides in students learning of content considering the population of student needs.

It is challenging to integrate technology while at the same time, consider the pedagogy and the content simultaneously through a TPACK framework. Today, most teachers are trained to incorporate technology via one size fits all professional development sessions which typically provide only an introduction to a tool and focus only on the technology itself and not the best practices for integration the tool into student learning.

There is no debating the fact that students need to be technologically savvy and as educators we are responsible for making our students college and career ready for the 21st century. With a wide range of applications available at our fingertips, educators need to determine which tools are the best aligned with content that will enhance the pedagogy for their students. Students have also culturally adapted to the world of smart phones where they can download an app to practice a particular science skill, sketch and rotate molecules, makes mechanisms, etc. (Williams, A., & Pence, H., 2011). While there are many advantages of using such tools, the traditional paper and pencil method should not necessarily be dismissed. For instance, when polled my students preferred assessments on paper over the computer. Even when providing students with the rationale behind computer assessments such as Graduate Record Exam (GRE) and vocational tests now being administered online, they still did not prefer this method and stated they needed to annotate the questions and wanted to interact directly with the text on paper. Additionally, students in my class preferred Lewis dot diagrams and drawing structural formulas in organic chemistry by hand over their technology counterparts. For programs that had the application or functionality to create molecules, often it was more cumbersome than drawing by hand and more time was spent learning how to use the program than the chemistry content itself. When considering this from a TPACK lens, the technology did not enhance student learning and thus the lesson needs revision.

In summary, when trying to incorporate technology into lessons, teachers should consider the content at hand, the pedagogical method that best suits teaching the content and the technology that would aide or be the mechanism of instruction for a particular group learners. As educators, we continue to strive to improve our instruction. It’s beneficial to reflect and think about why a teacher is using a particular piece of technology and ask if it is serving the function the teacher believes it to be. There are many pedagogical techniques available that do not necessarily require technology such as Modeling instruction™, POGIL®, and improvisation to name a few that for which I have been unable to find a technological counterpart that I feel is equally effective for my teaching environment. While the demands for technological applications for certain pedagogical techniques have been met by means such as zoom meetings with breakout rooms to teach concepts via a POGIL® activity, I would argue that certain populations of students learn better from the face to face interaction. Thus, there is not one singular approach that works but rather a variety of approaches that can be appropriate depending on what the content goal is for a particular group of students and the context.

References:

Glaser. R. (1984). Education and thinking: The role of knowledge. American Psychology, 39(2), 93-104.

Graham, R. C., Burgoyne, N., Cantrell, P., Smith, L., St Clair, L., & Harris, R. (2009).

Measuring the TPACK confidence of inservice science teachers. TechTrends, 53(5), 70-79.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. (2007). Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK): Confronting the wicked problems of teaching with technology. In C. Crawford et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education International Conference 2007 (pp. 2214-2226). Chesapeake, VA: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M.J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for integrating technology in teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017-1054.

National Research Council. (2000) How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Shulman, L. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4-14.

Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1-22.

Williams, A. J., & Pence, H. E. (2011). Smart phones, a powerful tool in the chemistry classroom. Journal of Chemical Education, 88(6), 683-686.

Having spent a career teaching high school science, I am now engaged with the world of elementary science. The adoption of the New York Science P-12 Science Learning Standards (NYSSLS) in December 2016 has apparently rejuvenated interest in elementary science. Recently retired (meaning time on my hands?) and involved with the transition to our new science standards based on A Framework for K-12 Science Education and NGSS, I was drawn into professional development opportunities. I’ve learned a lot about how students should learn science, reasons to shift to significant core ideas, how to incorporate engineering, provide meaningful hands-on experiences, and engage with phenomena. These standards should address the needs of all students, incorporate real-world scenarios and when possible be community-based. What really excites me the most about the NYSSLS is the impact this will have on our youngest learners.

Having spent a career teaching high school science, I am now engaged with the world of elementary science. The adoption of the New York Science P-12 Science Learning Standards (NYSSLS) in December 2016 has apparently rejuvenated interest in elementary science. Recently retired (meaning time on my hands?) and involved with the transition to our new science standards based on A Framework for K-12 Science Education and NGSS, I was drawn into professional development opportunities. I’ve learned a lot about how students should learn science, reasons to shift to significant core ideas, how to incorporate engineering, provide meaningful hands-on experiences, and engage with phenomena. These standards should address the needs of all students, incorporate real-world scenarios and when possible be community-based. What really excites me the most about the NYSSLS is the impact this will have on our youngest learners.